Research News

Researchers of our Genetics of Behavior Lab have shown for the first time that the kin-recognition and predatory abilities of the roundworm species Pristionchus pacificus can influence how these nematodes group together. Grouping with relatives may ensure that they have an advantage when it comes to food sources or protection from predators. This work, published in PLOS Genetics, will help to understand more about the significance of kin-recognition behaviors and their evolution.

Aggregation and cooperation among family members is a well-known behavior in many animal species and the benefits are obvious. But is cooperative behavior among relatives the first thing that comes to our mind when we picture little roundworms? Probably not. Indeed, some nematodes behave as solitary animals, while other species form aggregates to help them find food. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior in Bonn have been exploring these behaviors in more detail using a specific clade of the nematode species Pristionchus pacificus, a which are found on the top of a volcano on La Reunion Island and form groups with each other under laboratory conditions.

The little worm P. pacificus has been the focus of research of the Genetics of Behavior Lab, led by James Lightfoot, for several years. P. pacificus is omnivorous and uses teeth-like structures to predate on other nematodes. They are the first nematode species, in which a robust kin-recognition system has been shown. Thanks to these abilities, they do not kill their own offspring and close relatives. This kin-recognition system is also the basis of the social aggregation in this species, now shown for the first time. The system does not only distinguish between “related or not related” – it can even tell the worm how closely related another worm is.

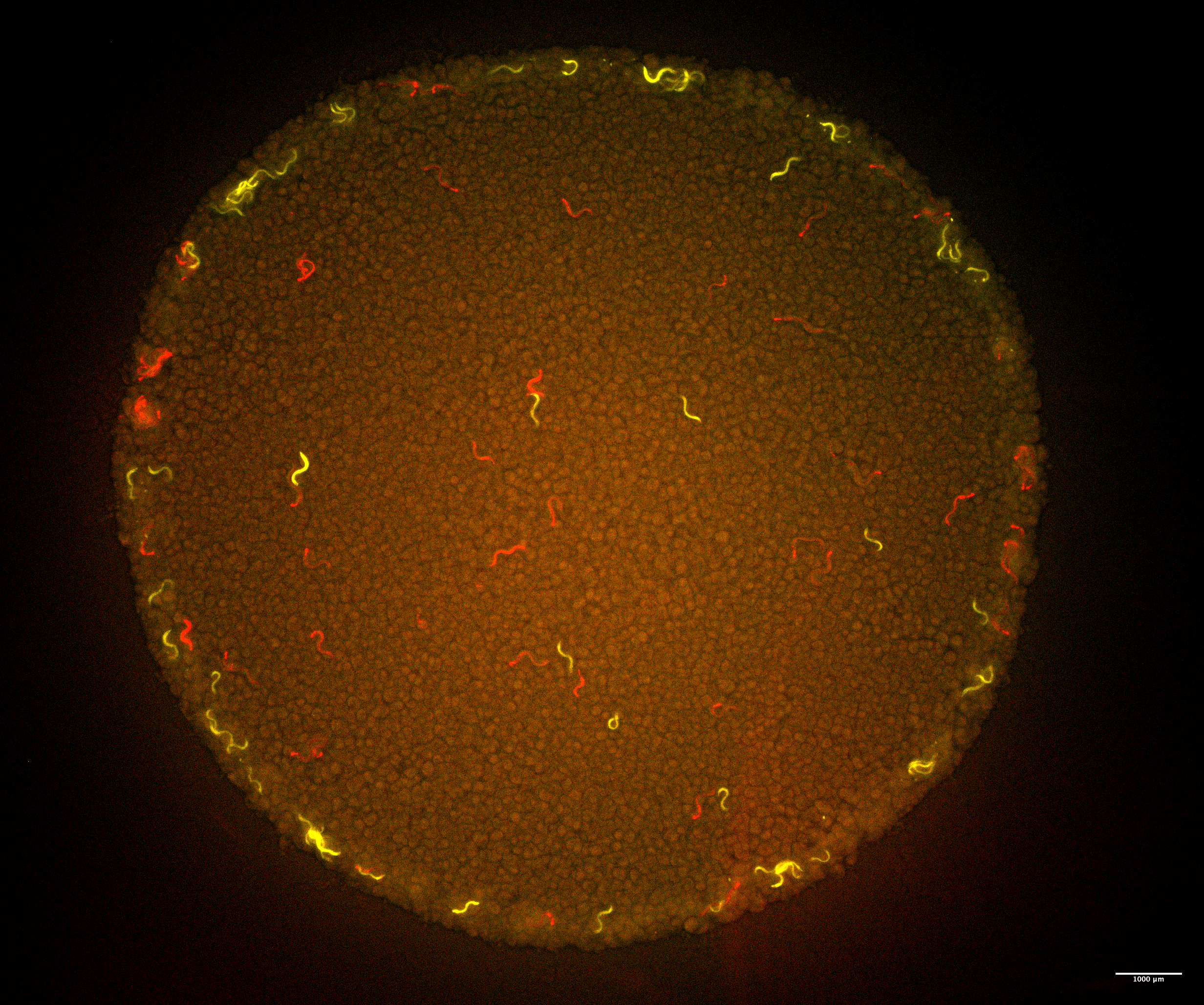

By performing assays where two strains that are either closely or distantly-related to each other interact on a small bacterial food lawn, the researchers showed that P. pacificus have a preference to aggregate with close relatives, while more distantly-related animals displace each other. “As these nematodes are also predatory, we also show that it is the predatory behaviors between non-kin strains that determine who groups with who” says Fumie Hiramatsu, the lead researcher of the study. Importantly, as P. pacificus is often found with other species of nematodes including the famous model organism Caenorhabditis elegans, the team also tested the interaction between P. pacificus and C. elegans. These experiments revealed that C. elegans were unable to aggregate well, while P. pacificus continued to aggregate together. “Thanks to its predation and kin-recognition abilities, P. pacificus is even able to disrupt the behaviors of other nematode species, which may be highly advantageous in its natural environment” says Dr James Lightfoot.

In the future, the researchers will explore how these interactions may also influence other behaviors, as well as the importance of the molecular components involved in kin-recognition in more detail.

To video interview with James Lightfoot